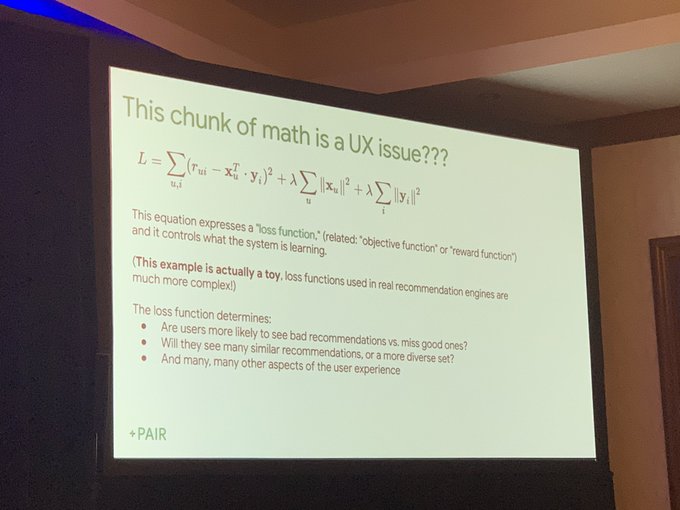

Machine learning loss functions are a UX problem, not just a math problem! Defines the end-goal of the system. #CSCW2019 keynote by @wattenberg @viegasf

Why more UX designers should attend research-oriented conferences

published

jan 12 2020

tags

design, user research, design thinking, ux research, conferences, ux

reading time

11 min

introduction

I’ve been a User Experience Designer in the healthcare domain for about four years now, and most of my work revolves around simplifying workflows and making medical devices easier to use for healthcare professionals. As I’ve built familiarity with the products and people in this domain, the inherent complexity and highly interdependent nature of the healthcare system is hard to escape. The diversity of tasks, people and systems that exist in this space, which all have to come together to provide quality care to patients poses a distinct challenge.

However, there is a silver lining, which is the research done in this domain, aimed at discovering the institutional and societal issues patients and healthcare professionals face on a day-to-day basis. It’s been crucial for me as a designer, coming from a non-medical background, to familiarize and empathize with this sophisticated space.

I’ve always been interested in attending research-oriented conferences, like CHI or one of the many IEEE conferences, but as a UX Designer, there have always been plenty of interaction design/product design conferences that I gave priority to. In the early stages of my career, the desire to learn more about the craft and the promise of learning from other experienced designers in the field always seemed more enticing. And surely, these have been very instructive about the path to good design work and have quietly vindicated my own thoughts about the process and the craft of design, which has been significant in dispelling my impostor syndrome.

With experience, I’ve learned to evaluate my work by the amount of intentionality I can bring into it, the more meaningful design decisions I can make, the better the solution is going to be. This approach forces me to think more broadly about the problem I’m solving taking into consideration the goals of the user and the business. And more deeply about the individual choices one needs to make while designing an interface, accounting for the subjective nature of our understanding and objective capacities as human beings. It’s the asking of questions within this framework that leads you to a solution that works. Although some of the answers are readily available, it’s usually the research that gives you a fundamental understanding of why things work the way they do.

a journey west

Austin was hosting CSCW2019, a conference on “Computer Supported Co-operative Work”, organized by Association of Computing Machinery (ACM) and regarded as, “..a premier venue for presenting research in the design and use of technologies that affect groups, organizations and communities.”

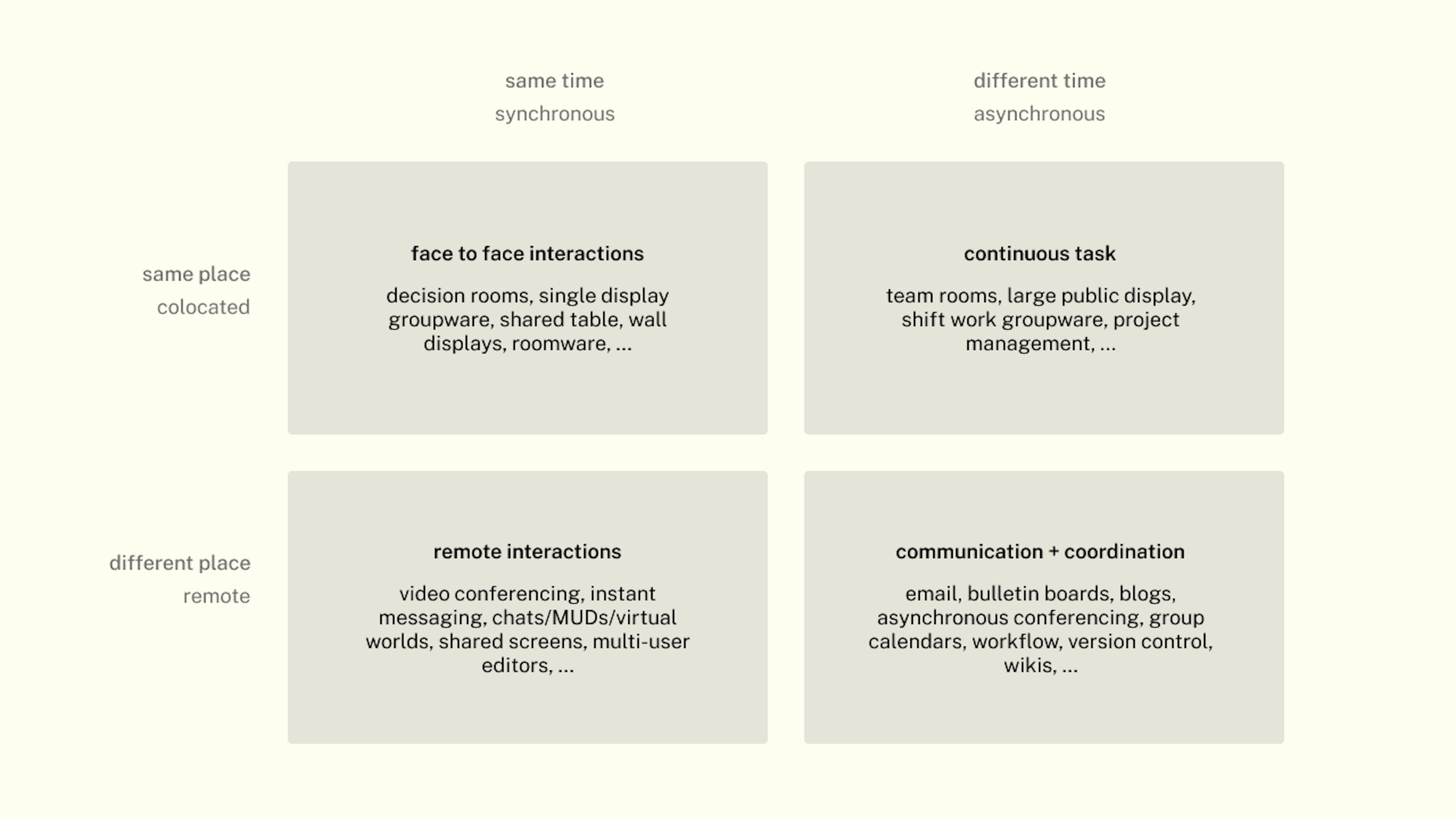

The term ‘Computer Supported Co-operative Work’ was introduced by Irene Greif and Paul Cashman in 1984. A seminal article on CSCW by Ellis et al., published in 1991, provides more background on the development of this field of study. The authors begin with a prediction — “Society acquires much of its character from the ways in which people interact. Although the computer in the home or office is now commonplace, our interaction with one another is more or less the same now as it was a decade ago. As the technologies of computers and other forms of electronic communication continue to converge, however, people will continue to interact in new and different ways. One probable outcome of this technological marriage is the electronic workplace — an organization-wide system that integrates information processing and communication activities.”.

The authors go on to define products that seek to support a group’s communication, collaboration and coordination as ‘Groupware’. Examples of groupware include — ‘Message Systems’, ‘Multi-user Editors’, ‘Group Decision Support Systems’, ‘Conferencing’ and ‘Intelligent Agents’ among others.

In 2019, this and more has come true. With the internet, we are more connected than ever and in the globalized state of our world, we can see this shift in the tools we use as well. Once siloed desktop applications are becoming collaborative workspaces, and major technology companies like Microsoft and Google are pushing to create seamless cloud-based platforms and smart assistants powered by the internet.

Contrasting this to Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) which focuses on supporting individuals in problem-solving, CSCW concerns focus on facilitating interactions between co-located and distributed groups of people and systems.

new perspectives

On Monday morning, after an uneventful journey, I reached the venue looking forward to the conference days ahead of me, mostly curious but still a bit anxious about what to expect. As I soon realized the keynote itself would have been well worth the visit.

“Participatory Machine Learning” by Fernanda Viegas and Martin Wattenberg from the People and AI Research (PAIR) initiative at Google talked about a more inclusive way of building ML solutions. This seemingly complicated topic was beautifully conveyed through the idea of ‘boundary objects’ — a sociological concept referring to information or entities that can link communities together and allow different groups to collaborate on a common task. We, as designers use boundary objects all the time — concepts or prototypes that we share with end-users and colleagues to build a shared understanding of what we are envisioning. These artefacts help create a framework through which we get feedback, leading us to a deeper understanding of the needs, desires and mental models of our users.

Similarly for AI, experiments like the TensorFlow Playground which explains how neural networks work through a visual and interactive playground and Facets — a tool which helps visualize training data sets — could allow more people to understand and engage with these complicated and often intimidating technologies.

The takeaway was a call-to-action, urging researchers and developers building AI tools to think about how to be more inclusive of people who don’t think in concepts of algebra or calculus; enabling them to participate in the conversation that is shaping this new and profound technology. A key example that Fernanda and Martin shared of how this collaboration might play out in the real world was SMILY, a human-centric, similar-image search tool for pathology. Although AI algorithms are great at solving relatively narrow problems at scale, they can often not compete with the deep understanding a human has of the context of a problem at hand (at least, not yet). Through careful human-centred design research, an interactive version of SMILY was developed, in which a pathologist can guide the algorithm to focus on specific aspects or characteristics of an image resulting in improved clinical usefulness, higher trust and likelihood of adoption. This example works to further the notion that collaboration between different disciplines can enable us to create solutions that are greater than the sum of its parts.

questions & answers

Machine learning is big in healthcare, and it’s application in diagnostics and treatment recommendations have transformative potential for healthcare and life sciences. But AI-powered tools are new, not only for end-users but also to people developing them. Concerns about the transparency, credibility and fairness of algorithms are challenges that this new technology must address to gain adoption and trust from its consumers. Couple this with imbalanced problems — datasets where one classification of data is overrepresented — it makes it harder to achieve a high level of accuracy and increases the chance of missing out on rare occurrences. It gets tough at the implementation level too. And this is especially challenging for healthcare, where the inability to find rare occurrences could be a matter of life and death.

So how do you make a system that users trust? How do you make it robust, so that when it has gained a user’s trust, it doesn’t fail them? How do you design a system that’s fair and transparent? Build it, so it’s explainable?

These are complex, abstract requirements that we need to work with — articulating them into specific design decisions which often vary from one application to another. It’s great that some companies have invested the time and effort in the creation of frameworks to make these concepts more accessible, however, it’s still early days, and it takes time, trial and error to apply such novel technologies appropriately to different domains and contexts. Although not directly analogous, consider the journey it took us to move from skeuomorphism in interfaces to richly animated interactions that we are so used to today. If that’s the case, then these are undoubtedly exciting times for us designers to re-imagine how we interact with products built using these new and profound technologies.

As machines become more intelligent, we have to start imagining them more like partners and collaborators and less as tools. Jonathan Grudin describes this very eloquently in his rich and comprehensive history of Interaction Design, From Tool to Partner . “It slipped in”, referring to a phase of human-computer symbiosis, “perhaps as we slept, when our devices, servers, and applications began working around the clock on our behalf, semi-autonomously, gathering, filtering and organizing our information. (…) It is not a balanced partnership. Our software partners can be frustratingly obtuse — and our frustration proves that we know it could be better. It will be better. We have embarked on a journey.”

Another paper at CSCW, Hello AI: Uncovering the Onboarding Needs of Medical Practitioners for Human-AI Collaborative Decision-Making” by Carrie Jun Cai et al “. explored how human-AI collaboration can be improved in the medical workplace. Similar to the mental models that medical experts form of their colleagues when seeking a second opinion, participants wanted to understand the medical perspectives and standards that their AI assistant embodied. They wanted to know upfront what was its design objective, it’s subjective point-of-view, and it’s known strengths and limitations. This is a paradigm shift in how users expect to interact with these technologies, transitioning from push-button tools to intelligent silicon-based colleagues.

out of the bubble

On the other side of AI and machine learning lie the humans and their data powering these technologies. As we reveal more about ourselves to our digital partners, what happens to our somewhat primal need for privacy and personal space? What happens when the most identifiable and immutable form of personal information, one’s genetic makeup, is exposed to undesirable parties? The implications to the privacy of people who have tried over-the-counter genetic testing services is certainly a conversation worth having as these technologies become more mainstream.

In the paper, “Becoming Part of Something Bigger — Direct to Consumer Genetic Testing, Privacy, and Personal Disclosure” by Jennifer King , her research brings to light a participant’s assumptions of anonymity, as well as their belief that their contributions to online genetic databases aid the public good, as key motivating factors for trying out genetic testing services like 23andMe. The participants, much like myself, were generally unaware of the potential risks to their genetic privacy as well as the impact of large scale genetic testing databases on networked, collective privacy. The idea that by sharing your genetic information, one is not only sharing their data but some part of their families as well, is something I did not consider immediately.

In another paper ‘Variations in the use of Electronic Medical Records: Role of Sociocultural Aspects’ by Ayushi Tandon ; consider how by merely displaying a patient’s insurance information (private vs. state), in an electronic medical record, can dramatically change the quality of care a patient might receive. Learning about the bias and stigma that certain communities and marginalized group of people face in society today was sobering, and humbling. It was incredibly reassuring to meet and talk to people researching these topics, who passionately believed in their work and wanted to bring these issues to light.

The empirical nature of some of the research presented at CSCW, the interviews, quotes, and vignettes have a visceral quality that helps connect and empathize with the people we are designing for.

A perfect example of this quality was reflected in the paper by Amy Cheatle et al. — “Sensing (Co)operations: Articulation and Compensation in the Robotic Operating Room” , also voted as one of the best papers at the conference.

“…When I operate, I don’t just operate with my eyes — you can also hear tissue when it’s getting cut. I’ve been like, ‘did you HEAR that?’ you know, when there’s something strange — so I think it involves every sense you have. You know it’s the hearing of it, it’s the touching of it — and it lets me know how easy a plane is going to be dissected if I just touch it, and it peels away like butter, or if it doesn’t move at all. There’s a lot to be gained that I feel I need as a surgeon. I like to touch tissue. It’s something I struggle with, with the da Vinci.”

The paper explores how the introduction of robotics, like the da Vinci robot , into the operating room reconfigures the sensory environment of surgery and how surgeons and their teams recalibrate their work in response.

In the day-to-day of designing complex machines and workflows, the ability to re-align with the people we are designing for, and the experience we might be replacing is invaluable.

new avenues

As the conference ended on its third day with diminishing crowds in the halls, slowing down from their usual electric pace, I reflected with a head full of ideas and a heart full of humility.

I was glad that I made the decision to attend. As a UX Designer, my job involves essentially two things, to understand the experience and apply this knowledge to create solutions that serve people. In the fast-changing world where we are pursuing the frontiers of technology, it would be irresponsible for us to not take a moment to consider the consequences of our decisions and ensure that the net impact is more positive than negative. I am comforted slightly knowing that I have met people and know of avenues that I can turn to when I have these questions.

Conferences have a way of initiating a journey, taking stories, slices of the world around us, and placing them front and centre of our attention. It compels us to look at things more closely, question them, understand them and to reflect on these new-formed perspectives, and apply it to the work that we are doing.

I would like to encourage you to take a second look at research-oriented conferences and consider attending. Although there may be bits that you don’t completely understand, I promise you will leave with a fresher perspective, new insights and nuggets of foundational knowledge that forms the bedrock of what we do as designers.

Cheers!

connect

built with/colophon